Something Good #98: Word Play

I started playing Chants of Sennaar on New Year's Eve, and for weeks it was almost all I could think about. Looking at my Notes app entries from the time, I find myself asking searching questions like, "Do we impose puzzles on the world, or is it actually made of them? Is there any difference?"

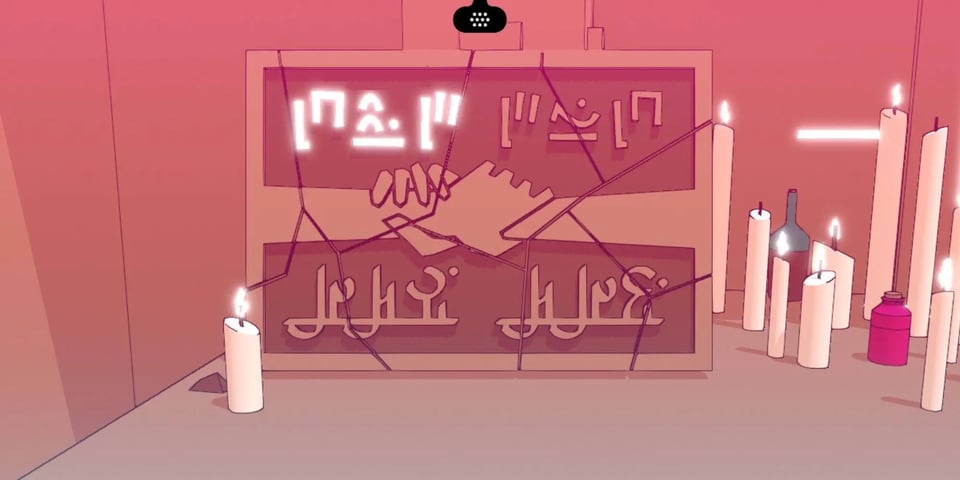

Chants of Sennaar is a video game created by a small team of French developers. The visual design takes cues from comic artist Jean Giraud, aka Moebius: big flat planes of colour, huge, enigmatic architecture that dwarfs the tiny human figures who dwell in it.

Language is the primary mechanism of this game, specifically the act of translation. You start the game as a silent visitor to the lower levels of a mysterious tower. Soon, you encounter other people, but you can't understand what they're saying. Their spoken language is unintelligible, their words appearing onscreen as cryptic glyphs.

Context clues, which range from observing the other characters' behaviour to clever environmental storytelling (graffiti, murals, shop signs, etc), help you fill a notebook with the words' meanings. Or at least, your best guesses, though the game is generous about telling you when you're successful, or even close.

But even before you master this first language, you come across another group of tower inhabitants. They are armed like palace guards, and they speak yet another language, which its own set of visually distinct glyphs. They won't let you by, and you don't understand why not. To progress up this mysterious and evidently Babel-like structure, you're going to need to understand how to talk to them, too.

Doing so is going to require interpolating some of your knowledge of the first language. But—and this is important—these languages aren't one-to-one grammatical equivalents. Not only is the vocabulary different, but the very rules the words follow. Subject/object placement, pluralization, and other basic concepts might manifest in very different ways.

And this is where the game gets really interesting. Because—

Hold up. What I'm going to say contains, strictly speaking, some spoilers for Chants of Sennaar, but very abstract ones. Still, I want to give you the chance to skip them. Just scroll down to the next image and you should be good.

(Ready?)

Right. What becomes clear as you climb the tower is not only do the different languages have their own unique vocabularies, not only do they have different grammars, but they have their own particular, context-specific worldviews, and that colours not only how they see the world, but how they speak. Understanding the groups' unique perspectives is the key to understanding what they say. One culture's "fool" might be another's "brave warrior." Sufficiently advanced "scientists" might be indistinguishable from "fairies." Once that clicks, Chants of Sennaar becomes much more than a cryptographic puzzle.

There's a genre of game known as the "metroidvania," a portmanteau of the two series that helped define a specific style of game design, Metroid and Castlevania. In these games, you explore large, complex, non-linear spaces (castles, space stations). Frequently, you'll find your progression impeded by an obstacle, such as an un-openable door, or a chasm that's too wide to jump across. What the game wants you to do is to go explore some more until you find an ability that allows you to get past the obstacle (like a chasm-spanning double-jump), then retrace your steps and return back to where you were blocked. It's a tremendously satisfying game loop. Chants of Sennaar is like a metroidvania, except that your progress is only impeded by your own knowledge. Go back, explore, learn some more, and you come back able to talk to the palace guards and understand why they wouldn't let you by, and what you might have to do to get around them. This produces a sense of exploration that feels almost internal—like you're wandering through your own mind, looking for clues.

Video games can be said to be about many things. But what sets them apart from most other aesthetic experiences is the act of active exploration. This can come in many forms. You can explore an imaginary space; explore a relationship between two characters; explore a collection of clues in the hopes of finding a story there. (Whenever I wander around a museum, I often feel like I'm playing a video game, "clearing" each room of points of interest before moving on to the next.)

By exploring, we open up new areas, new stories, new experiences. But most of all, we open up more. More time to play, more of the wonderful experience of making progress or solving a puzzle. The flow state we experience when we game is above all a manifestation of the desire to persist. To not only keep playing, but to keep living. (The most precious commodity in video games used to be "more lives.")

It's not really possible to "die" in Chants of Sennaar, but it is possible to get stuck. The result is the same, though—the inability to keep "moving forward" of course being the simplest definition of death. Unlike games where you're asked to develop skills based on muscle memory or develop an optimal strategy, progress in Chants relies on solving discrete puzzles which for the most part have specific answers.

It's essentially what we call "lock and key" design, sometimes disparagingly—meaning that every puzzle (lock) has a single solution (key) that will open it. But in this game, that doesn't mean that there are no meaningful choices to be made; rather, the game's rigid structures allow a beautiful expression of play on the most abstract level. There may only be a single "key" to unlock a certain puzzle—a phrase to repeat, a machine that can only be operated if you can read and understand its controls—but the answer is always a piece of knowledge you must somehow learn.

How you do that is entirely up to you, the player, and the way your brain likes to work. For me, it involved wandering the halls of the tower, visiting its locations over and over again, far past the point of extracting any more useful information, just letting myself roam and think. (Not unlike how I solve problems in real life.) Usually, I would eventually put the game down, but never with a sense of frustration, just an intuitive sense that my subconscious mind would keep working on the problem in the background.

When I returned a day or so later, I was almost always able to solve the puzzle, usually without any conscious effort during the interval I was away. Observing my mind at a distance in the moment of insight as it produced the solution was always thrilling. Those moments are some of the most satisfying I have experienced in gaming, and a pure distillation of the beauty of exploration.

In his book The Beauty of Games, game designer and academic Frank Lantz talks about his fascination with the ancient game of Go, which, with its three simple rules, has produced thousands of years of profoundly deep gameplay.

Go is thought made visible to itself. That is not to suggest that Go provides some kind of mystical, transcendentalist experience in which thought is fully present to itself. Instead, Go offers opportunities to catch partial glimpses of the operation of our own mind. It opens a window that invites us to peer inside and think about how we think.

This was my experience playing Chants, and many of the games that have meant something to me.

Chants of Sennaar is now available on PC and most consoles.

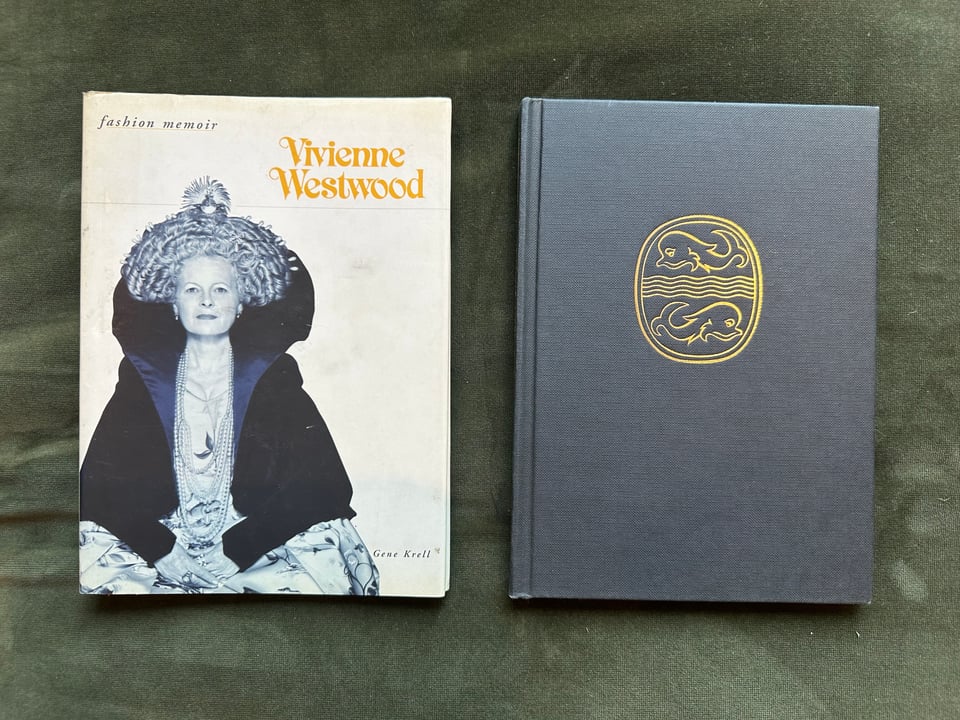

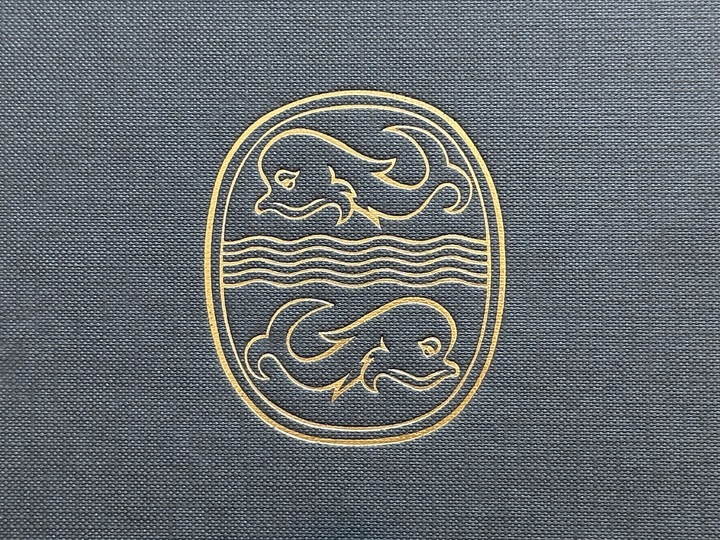

This week's #nojacketsrequired comes courtesy of my friend Melissa, whose bookshelves I shamelessly plundered in search of clothbound gold. And what a discovery I made! I can think of few better examples of a gorgeous book cover design smothered by a tasteless jacket.

Just look at that.

As always, send your rescued covers to me at slutsky.mark@gmail.com.

Bonus track(s):

This has been Something Good. The transition to Buttondown continues; if you spot a bug or broken link, please let me know. We're still reading A Time of Gifts over at Barely a Book Club; stop by and join us, there's plenty of time to catch up.

If you enjoyed reading this edition, please tell a friend or subscribe below. (The subscribe button might be invisible. We're working on that. It's right here:

Add a comment: