Something Good #101: This Is What the KLF Is About

John Higgs on chaos, magic, money and the band who burned a million pounds, the KLF.

Sometimes a book comes along that connects all sorts of glimmering, disconnected ideas, weaving them into a constellation of meaning that feels like it had always been waiting there invisibly. Often that book is by U.K. journalist John Higgs, whose The KLF: Chaos, Magic and the Band who Burned a Million Pounds will be published for the first time this week in North America. This is a book that resonated deeply with me when I first read it, to the point where I felt like I had to lend it to everybody I know, and I was thrilled when Higgs generously agreed to speak with me for Something Good.

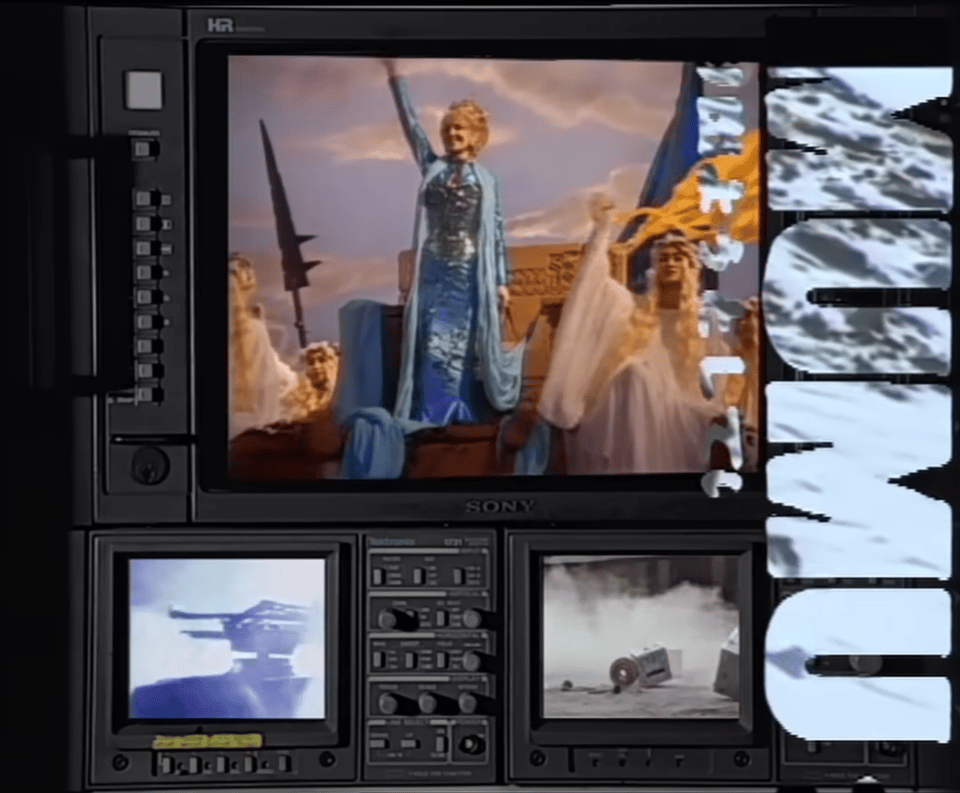

The KLF, a duo consisting of former A&R man Bill Drummond and DJ/electronic musician Jimmy Cauty, blipped on the American charts with their deeply strange hit single “Justified & Ancient (Stand by the JAMs),” a 1991 “stadium house” dance track steeped in the rave revolution, with country music legend Tammy Wynette singing cryptic lyrics about lost Atlantean civilizations, ancient conspiracies, and ice cream vans.

This was well before any of this made any kind of commercial pop music sense, and watching the frenetic, joyful, utterly incomprehensible video on MuchMusic as youngster made a deep impression me, even if I really had no idea what the fuck was going on. It resided in my brain as I was drawn into the kind of alt-culture bubbling up at the time, the Illuminatus! books of Robert Anton Wilson and Robert Shea, the comics of Alan Moore, the luminous, mischevous ambient house music of the Orb—all things Higgs would later connect in his KLF book in ways that made perfect sense in retrospect.

The KLF was more than just a hit singles band; they were, and continue to be, a funny, confounding, confusing art project extending into film, performance art, and magic ritual. They weren’t just huge hit-makers; they wrote a book how, called The Manual, explaining how to produce a number one single, which some best-selling bands have claimed to have followed with successful results. At the 1992 Brit Awards, where they were awarded Best British Band,1 they shot machine guns loaded with blanks at the audience, and left a dead sheep on the steps of the post-party. In 1992, at the height of their success, they announced their retirement from the music industry and deleted their entire back catalogue, removing their music from the market for the following 23 years.

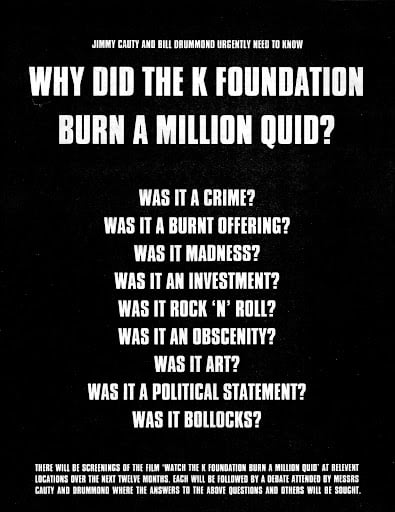

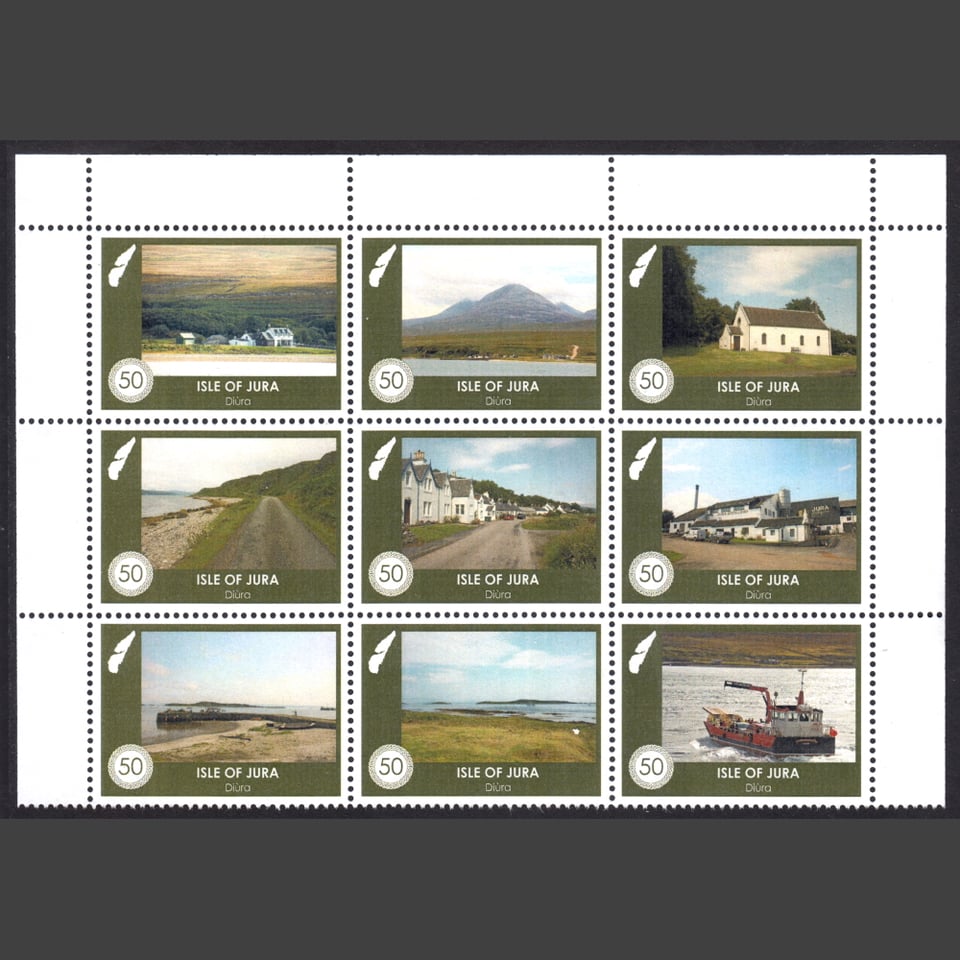

But the event that cemented their legend, and notoriety, took place on the Scottish island of Jura in 1994, where they invited a lone journalist to watch them burn one million pounds in cash, allegedly most of what they had left over from their hitmaking days. It was an act that they themselves couldn’t explain. They toured the country booking halls in small towns and asking the often irate citizens who showed up why they thought they’d done it. No answer seemed convincing, least of all to themselves.

One result of the post-truth era is an understandable literal-mindedness in the world of non-fiction writing. John Higgs’ thought-experiment journalism is not like that; it’s exploratory, un-cynical, often asking what if instead of declaring what is. This makes him, in my view, the perfect person to answer the KLF’s million-pound question for them.

To Higgs, the KLF were characters in a story much larger than these two men, who found themselves on the precipice of fame and power at a hinge moment in our civilization between the Cold War and the internet era. Their act of destruction, so contrary to the values of capitalist society, inaugurated the coming millennium through an incandescently powerful symbolism that continues to resonate.

I can remember turning on the TV in the early ‘90s and seeing the KLF’s “Justified & Ancient” video, and just being totally confused. This crazy collage of Tammy Wynette, wild costumes, dancers, cryptic ritual, random text all over the screen, a submarine… I had no idea what I was looking at and to some extent, I think I still don’t.

Absolutely. They stood out so radically from everything around them. Words like “justified” and “ancient,” you just don’t hear those words in pop music. Those aren’t pop music words. They come from somewhere completely different.

Reading your book made me realize that, sure, I didn’t understand what was going on, but on some level, maybe neither did they.

That’s probably true for a lot more people than we think!

Usually, in Western culture, the artist is this determined, intentional figure who knows exactly what they’re doing, even if nobody else does. But I love the idea that they were just as bewildered as I was.

A lot of it is about intent, or rather, a lack of intent; about trusting the artistic impulse that drove them. Allowing it to flower without your rational left brain critiquing it out of existence the moment it appears.

There's always a million reasons why you shouldn't do something and it'll be terrible. But if you just shut that voice off, and allow the thing you're doing to become what it is, it will take you to places that no committee would ever sign off on, or no one else will ever really quite understand. But it can take you to some phenomenal pieces of art.

So what was your introduction to the KLF? Here in North America they were pretty much a novelty that barely missed hitting the top 10, but never close to the cultural force that they were in the U.K. at the time.

They were inescapable. They were everywhere. They would have number one after number one after number one. They'd be on Top of the Pops, which was the big music program, and in the newspapers and things like that. They were a big part of culture.

I was more of metal kid at the time. So dance music was by definition wrong in some way, and I wasn't paying that much attention to it all.

But then they burnt the money. There was an article in the newspaper that came out that was to be followed by this almost deathly silence in which nobody had anything to say about it. But I just remember reading that article, by a writer called Jim Reid. I read it all the way through and I just thought, I'm just going to have to rip this out of the paper and keep this because it didn't make sense to me but there was clearly something there.

I’d never clipped an article or anything like that before. It was the very first time that I'd come across something that I knew was important to know about in the future. When you come across something that doesn't make any sense, it's a sign that the limitations of your worldview are being run up against. It's always things that are worth exploring, just to give you a clue of the vast expanse of all the things that you don't understand. They're coming from that world. Your world is incomplete. Your way of looking at everything doesn't contain the philosophies that theirs do.

It just stuck with me. When something makes sense, you can read about it and go, that's interesting, I'm fascinated by this… but you can then move on. But it’s when things just don't make sense, that they just sort of stick in your craw and you can't really forget about them and move past. And from that point on, certainly the next 17 years until I actually wrote that book, it was always there, the notion that there was something interesting in the KLF that I would like to understand and I didn't understand.

And then I heard it said by people close to them that the KLF actually stood for “King Lucifer Forever” or “King Lucifer's Force,”2 one of the two. And it was like, you don't get that in pop music very often. That's something odd that’s going on there. And again, that kept me trying to make sense of it. In fact, the whole book really exists in the belief that I could then get it out of my head and move on. Writing books is good for that. You can just move on afterwards. But here we are about 13 years later still talking about it. So it's always been a presence with me. Ever since the book came out, I don't think a week's gone by without people asking me about it.

The experience you’re describing sounds to be very similar to their own reaction to the money burning, a kind of obsessive bewilderment that led them to go on speaking tours where they’d ask the public why they thought they’d done what they’d done, and to define it. That’s such a wonderful detail of the story.

I know, isn't it just? And it also gave me the excuse to write the book, because they asked for a reaction. So I felt morally justified in just coming up with my own reaction without seeking permission. They're not the sort of band that you can paint a picture of by asking nicely and doing things correctly. You’re trying to capture the spirit of them. So I wrote the book without contacting them at all. That’s a weird thing to do, but oddly, for the KLF, it makes total sense.

The way they’ve been remembered in a lot of ways, or at least how they were portrayed at the time, was as these master media manipulators, these art pranksters. But the portrait you paint of them doesn’t quite fit that description.

No. Again, it's people not quite understanding what's going on. It's people butting up against something that doesn't really fit inside their philosophies and grasping for an explanation.

The idea that they knew what they're doing, and that they were skilled manipulators of the public, is one that a lot of people went for. But, you know, there really isn't much evidence for that, and an awful lot of evidence against it. Pretty much every interview that they gave, it’s very clear that they really don't know what they're doing or why. There's never any sort of glimpse of a master plan in the background or anything like that.

There’s this idea that you might not act, but be acted through in some way. I don’t want to get too mystical about it, but I’ve always liked the idea that genius is sort of a ghost that lands on your head for a little while and then flies away, leaving you unsure of what exactly happened. I couldn’t help but thinking of that, reading the book.

I certainly like the idea that things act through people. Big, large historical changes like the creation of the internet or the Beatles…

Or the Cabaret Voltaire, which you mention in your book as an antecedent…

Yes, absolutely. Those things that really do change culture and do sort of change the world; when you get back and you look at them in context, you can see a story, you can see something beginning and emerging and evolving.

When you drill down into individuals in that chain of connections, none of them have that big picture, none of them are consciously working towards the creation of what we see in history. It's probably a lot more common than we think about, that these huge shifts or changes that make narrative sense in hindsight, we're just blind to at the time.

I’m fascinated by moments where there’s an efflorescence of creativity, or revolution, and then the moment dissipates and everyone who was involved in it—because it's usually a group effort—is left sort of wandering the earth for the rest of their lives wondering what happened.

Yeah, I think it's probably more common than most people suspect. I think it could be for many people, when they get to a certain age, there's something that's happened to them, maybe in their youth or many, many years earlier, that they're still just fixating on because they know that there's something significant about it, if they could only just see the bigger picture.

You talk about the early ‘90s as almost a sort of inflection point, a liminal space between explicable realities—the same way reality was completely different for people before and after 1914, for example. Do you feel like those intervals between consensus realities are coming at a faster and faster pace?

It's definitely very, very different world now than it was in the 1990s. I think when we tend to look back at that time, we've got quite a sanitized version of what the ‘90s were. I think what's significant, in terms of culture, is that it was still the age when people sought out the good stuff. There wasn't much, so you'd go hunt, you'd actively be searching through record stores to try and find a rare thing, or you'd be going through the TV Guide and marking down the one program that looked interesting in the week. Or you’d hear of a book, but could never find it, but you’d always be trying to hunt it down.

Now, all of culture is there. Spotify has got the entire history of recording music, pretty much every TV program is available. Social media is desperate for your attention.

I guess what I mean is, do you feel like—and this is a question I don't think anyone can actually answer as we live through it—are we in a chaotic interval between things that will eventually congeal? I feel silly even asking this question because it's so.. ontological. Is this a liminal moment or is this just reality going forward?

Yeah, this is reality going forward.

I think a lot of the 20th Century was an interval between a hierarchical view of the world and the network view of the world that we are now. The hierarchical world of the view where it didn't really matter who you were, what you were like, or what you did, it mattered what your station was. It mattered if you were a duke, or a stable boy, or a doctor.

We thought at the time when that fell apart, with the rise of the individual and the individualism that marked the 20th Century, that this was the new thing, the goal of human society. But it was just a little pause between these centuries of hierarchical thinking and the future of this networked world going forth, where the idea of the individual we now know is insufficient to explain anything.

It's not just you, it's who you're connected to, it’s what reputation you have. You see yourself as part of a much larger thing than just a simple isolated individual who's unconnected to everything.

We’re more entangled.

There’s a big shift in how we understand ourselves that rose up particularly after the iPhone and everyone had the networked internet in their hands.

This book is about the period before all that, when the worldview was falling apart and everything had really been tried. The ‘60s tried loads of utopian thinking, the ‘70s tried loads of hedonism—you know, maybe that could be our goal. The ‘80s was much more materialistic. Maybe money is our goal. That search for that single North Star to guide us to how we should act in the world.

They’d kind of all been tried, and failed, by the time the ‘90s came about. That whole slacker, Generation X thing was a rejection of the notion that we did have the idea of a fixed point to organize our lives with. So the ‘90s was very realistic, but it was very nihilistic. The idea that the voice of the generation was the guy who shot himself… it’s dark, this is dark!

And then the idea that pop stars could burn all the money they made because it's tainted, or something like that. I think it was an odd time, a very, very strange time. But it was the end of one wave of history and the digital world is a completely different sort of thing that came in after it.

The KLF: Chaos, Magic and the Band who Burned a Million Pounds will be released in North America by Blackstone Publishing on July 9.

You can also buy an apron commemorating the event, designed in collaboration with John Higgs. Here’s me proudly showing off mine. In addition to the apron, I highly recommend his books Stranger Than We Can Imagine: An Alternative History of the 20th Century, and the recent William Blake vs the World.

This week’s #nojacketsrequired comes courtesy of myself. Michael Korda is the former editor-in-chief of Simon & Schuster and the nephew of both Alexander Korda and Zoltan Korda, Jewish Hungarians who attained a great deal of prominence in the mid-century film industry. A memoir of this very interesting family, I look forward to someday descending deep enough in my book pile to read it.

Bonus track:

Things are going very well over at Barely a Book Club, where we’ve just started our fifth selection in our series of travel books about places real and imaginary with Dervla Murphy’s Full Tilt. I highly recommend you read friend of the newsletter Roxane Hudon’s essay about this gem, which follows Murphy’s trip from Ireland to India on a one-speed bike, if you haven’t already.

Otherwise, I’m reading, finally, Mervyn Peake’s Titus Groan, a book which I’ve known about for decades but had never gotten around to, to which I say… what the hell was I waiting for?

More on this later. If you like Something Good, please tell a friend or subscribe right here:

A farmer would later dig up the award statuette somewhere in the vicinity of Stonehenge.

Other alleged meanings: Kopyright Liberation Front, Kings of the Low(er) Frequency, Keep Looking Forward, Kevin Likes Fruit.

Add a comment: